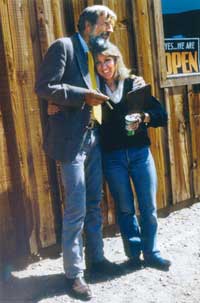

Ed Abbey and Vicki Barker |

There are times in life when you meet a legend before they are legend, and you sense it. Such was the case with Edward Abbey.

I’ve met, conversed with or interviewed a few legendary figures in my time -- actors John Wayne, Jimmy Stewart and Kris Kristofferson among them, not to mention writer Norman Mailer and the murderous Lafferty brothers of Utah. But Abbey tops my list because, as a writer and lover of the desert, he was a kindred spirit I chanced to meet for the first time in the very setting of my favorite book of all time, “Desert Solitaire.”

This month, “Desert Solitaire” is being celebrated as Abbey’s literary masterpiece and Abbey’s friends and family are sharing stories about the late author, self-proclaimed anarchist and wilderness protagonist, at the first Moab Confluence Writers Conference in Moab.

At a panel session (open and free to the public, see Events Calendar, this issue) titled “I Remember Ed,” a handful of those whose claims to fame include intimate knowledge of the philosophical rebel and desert lover are opening their hearts and dipping into memory’s well for others who want to know more about Ed than the couple dozen books that he has written and a couple of dozen more by others have so far allowed.

No doubt more books will follow, and more sharing of experiences. This writers conference, revolving around Abbey with a focus on “Desert Solitaire,” is long overdue. May more follow.

While the list of panelists as of press time was small -- presumed to be the closest of friends and family of Ed -- any audience who gathers to remember the voice crying in the wilderness would surely contain a great number of fans, admirers, friends and familiar others who aren’t particularly inclined to “kiss and tell,” and hopefully some foes who would lend a little spice to the encounter. After all, Abbey, whom some proclaim today as the founder of the Green Movement, was also heatedly denounced in some parts -- especially Grand County -- as a radical environmentalist and eco-terrorist.

If my father were alive, you would find him in the audience expressing his admiration as an artist and teacher for Abbey’s artful prose, but berating the former park ranger for opposing road development in the parks. My dad was a World War II vet, and along with his “Dear Sam” venting, he submitted an editorial cartoon of a soldier on crutches, one leg amputated, gazing into the vastness of the river confluence in Canyonlands National Park -- able to get to the viewpoint thanks to a new asphalt road.

Abbey and my dad had exchanged arguments in local letters-to-the-editor in the late 1970s, a few years after “Desert Solitaire” and “The Monkey Wrench Gang” were published; then agreeably rehashed their points of view in an impromptu meeting over breakfast at Milt’s Stop ’n’ Eat one day. As dad tells the story, Milt Galbraith greeted Abbey, who’d entered the eatery just as my parents were sitting down. “Ed who?” my mother asked, turning to see who’d lit up Milt’s face. “Well, it was Ed Abbey, my ‘friend,’ the writer of books,” Dad said.

“So you’re Dwain Barker,” said Ed. It was Election Day 1977 when my dad wrote to me. “You’re probably wondering why he would greet me in such a way, and here’s why,” he explained. “A couple of weeks ago, Ed wrote a letter to the editor expressing his feelings about wilderness. One of his statements was that we must make room for the wildlife, so I answered his letter with one defending our stand that humans come first.” “So you’re Dwain Barker,” said Ed. It was Election Day 1977 when my dad wrote to me. “You’re probably wondering why he would greet me in such a way, and here’s why,” he explained. “A couple of weeks ago, Ed wrote a letter to the editor expressing his feelings about wilderness. One of his statements was that we must make room for the wildlife, so I answered his letter with one defending our stand that humans come first.”

“Anyway, he was very interested in my point of view, and he thanked me for reporting in the paper that I had read both his outstanding books,” my dad concluded. “I really enjoyed talking to him in such an informal setting, and when we got up to leave he wanted to keep in touch with me…He seemed to be a very down-to-earth character.”

My father knew I admired Ed Abbey -- in fact, I’d urged him to read Abbey’s books. He promised to send me a copy of “that nutty letter” he’d written to the paper, “for you to cut to pieces.”

“I’ll also send the nutty cartoon,” he wrote, adding: “It was of great satisfaction to have some of the invironmentalists (sic) come back at me on it. One even submitted a cartoon which Sam wouldn’t print…”

Just as my father felt great satisfaction making wilderness defenders defensive, I derived great satisfaction over the years as a journalist writing reports on proposed developments that threatened to be highly destructive to the environment -- a nuclear-waste facility, toxic waste incinerator, and highway through the Bookcliffs among them -- that were defeated. In some cases, activists were incited to a little monkey-wrenching to get their point across -- pulling survey stakes out of the ground at the proposed Cisco incinerator site, attempting to block bulldozers clear-cutting pinyon and juniper trees at Amasa’s Back, paint-balling the new McDonald‘s billboard until the franchise quit advertising as “Moab‘s Other Arches.”

I’d met Ed the summer before my father wrote of him, and later shared yucks and drinks with him and campground ranger Jim Stiles at Devils Garden the year of the U.S. Bicentennial, when I worked as a park aide at Arches National Park. I’d already fallen in love with Abbey’s writing years before, smitten by “Desert Solitaire,” which I’d read while working as a receptionist at the new federal building in downtown Moab, fresh out of high school.

While reading “The Monkey Wrench Gang” in “the monkey cage” (which the rangers called the entry station at Arches), the author himself drove up one day, grinned and introduced himself. I insisted that he go on through for free, and he asked what I was up to in that tiny wooden shack. He seemed startled and pleased to hear that I had actually been deep into his book. “See you later!” he exclaimed, and drove off.

Indeed. Later, at his request, in “an act of opposing authority,“ I shunned my assigned duty of manning the front desk at the Visitor Center and led Ed and a group of college students on a field trip through the Fiery Furnace in late August. Having packed in a new journal, I wrote: “What better way to begin this volume than in the shade cast by a mass of rock in the Fiery Furnace? 1:20, and Ed Abbey is laying about 15 feet from me, surrounded by seven others in like positions. This man does have a strange appeal. I’m pleased to see he is younger, taller, handsomer and more amiable than I’d expected.“

Over the years, I tracked Abbey’s writings and writings about Ed. At one point, I wrote him a letter appealing for help getting an alternative newspaper started in Moab. We met for breakfast in Moab, and he suggested talking to Stiles. I already had. At Abbey’s last autograph party, in November 1988, he greeted me with a big bear hug and gave me a copy of his “semi-autobiographical” book, “The Fool’s Progress.”

Inside, he had inscribed: “For Vicki (with admiration), from her old fan & admirer, Ed Abbey.” He died several months later, in March 1989. It’s been nearly 20 years, but I still remember Ed, and I am grateful that his words in defense of wilderness live on. |