Geology HAPPENINGS April 2018 |

||||||||||||

| The Kayenta Formation: Ancient Rivers and Modern Trails By Allyson Mathis |

||||||||||||

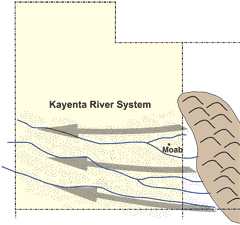

Like all rock layers (formations), the Kayenta Formation contains information about how it was formed (e.g., the environment in which this sedimentary unit was deposited). It also erodes into characteristic landscape features. The Kayenta’s ancient environment consisted of a series of broad shallow rivers flowing across arid lands in what is now Utah. Today, the Kayenta Formation makes step-like ledges and rocky surfaces that are followed by many trails in the Moab area. The Kayenta Formation also holds up the rims of the area’s deepest canyons. Anyone who has spent time in the backcountry around Moab has experienced the Kayenta firsthand, whether they have driven the Moab Rim, biked the Whole Enchilada or stood on the rim of Dead Horse Point. The Kayenta Formation was deposited approximately 190 million years ago during the Jurassic Period when dinosaurs roamed what is now Utah. In fact, it is easy to see dinosaur tracks in the Kayenta near the start of the Poison Spider Trail off of Highway 279 (Potash Road). At the time, the mountain range known as the Ancestral Rockies stood east of Moab and rivers flowed west from these mountains towards the seashore, which then lay in eastern Nevada. These rivers and streams carried sand and silt that was deposited all across southern Utah. Ultimately, the Kayenta sands were buried by other sediments, and later cemented by minerals in percolating groundwaters.

The Kayenta Formation is between 250 and 400 feet thick near Moab, and is mostly dark brownish red, although the color can be variable. Careful examination of the Kayenta layers reveals information about the sandy fluvial (river) system that deposited them. The thin beds contain low-angle cross beds that provide evidence of currents in these ancient rivers. Flowing water stacked up ripples of sand and swept them downstream along channel bottoms; each ripple leaving a thin, climbing layer of sand producing layers inclined to the main layers. This inclined layering formed is known as cross-bedding. It is also possible to see river channels that have been filled in by sand stacked on top of one another in vertical exposures. In the upper part of the Kayenta Formation, larger, steeper cross-beds indicate the localized sand dunes were forming as the climate dried. Eventually, the area dried so much that eolian (wind-blown) deposition took over. The massive dune field that followed the Kayenta river system became the Navajo Sandstone.

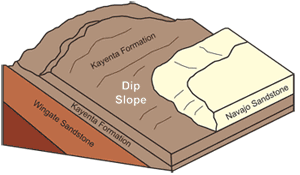

The Kayenta Formation is located between two of the most prominent cliff-forming rock layers in canyon country. The Wingate Sandstone, immediately below the Kayenta, commonly forms vertical cliffs and is one of the most prominent cliff-forming units on the Colorado Plateau. The Navajo Sandstone above the Kayenta forms steep rounded domes and vertical cliffs that can be as inaccessible as the Wingate cliffs. Thus, the more stair-step Kayenta layer provides access for hikers, bikers and jeepers.

Sometimes the Kayenta forms a vertical continuation of the Wingate cliffs, with the Kayenta section discernable as thin ledgey layers in the upper part of cliff-faces. This harder Kayenta cap forms the bedrock surfaces of many square miles of mesa tops in places such as the Island in the Sky, Dead Horse Point and Canyon Rims Recreation Area. In fact, the Kayenta is probably exposed at the surface more than any other rock layer in the vicinity of Moab, although its relatively subdued scenery means that it is noticed less than some other rock units.

Getting to know the Kayenta Formation is a good way to make the connection between the geologic present and the deep geologic past. The hard, thin, step-like sandstone beds in the Kayenta Formation result from their deposition in wide river channels nearly two hundred million years ago. In turn, appreciating the Kayenta Formation is a good way to develop an understanding of why trails are where they are, because in a landscape dominated by sheer cliffs, the Kayenta’s thin ledges offer relatively accessible terrain. The Kayenta Formation may not be as flashy as some of Moab rocks. The Kayenta’s dark reddish brown ledges are not as impressive as the tan domes of the Navajo Sandstone, the orange-red fins of the Entrada Sandstone or the colorful hills of the Morrison Formation, but they are just as essential to this spectacular landscape. We will learn more about other rock layers in future issues of Moab Happenings

|