|

| Determination Towers is in the Entrada Sandstone |

Mesas, buttes and spires are found throughout the red rock country surrounding Moab: Bridger Jack Mesa, Junction Butte and Castleton Tower are just one example each of nearby mesas, buttes and spires. These landmarks star in many of scenic photographs taken of the area. They are also destinations along trails and four-wheel drive roads and peaks that rock climbers strive to scale. Because these features do so much to define the character of the

|

| Balanced rocks, spires and hoodoos in Arches National Park, all capped by the Entrada Sandstone. |

landscape of southeastern Utah, this month’s Geology Happenings will explore them and how they came to stand as sentinels above the surrounding canyons.

Like almost all landmarks in canyon country, mesas, buttes and spires are formed by erosion. Generally, rocks that are resistant to erosion, such as sandstone, cap these promontories. These harder rocks form vertical cliffs at the top, while softer rocks like shale and siltstone make up gentle slopes near the base. Vertical fractures (called joints), that are present in the sandstones, are another key to the development of these features. As the softer shale and siltstone below erode more quickly, they undercut the harder cap rocks, which ultimately break off in large slabs along the fractures systems. The role that rockfall plays in sculpting mesas

and their smaller geologic kin is evident in the form of boulders and other debris that litter the slopes below, sometimes completely obscuring the softer rock layers underneath the cliff-forming ones.

|

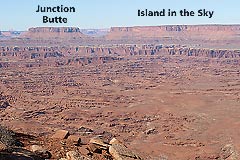

| Junction Butte and Island in the Sky as seen from near the Needles Overlook |

Mesas are wide, flat-topped mountains with steep or vertical slopes that stand significantly above the surrounding country. In Spanish, the word “mesa” means table, which aptly describes the broad horizontal summits of these landmasses. In fact, mesas are also sometimes simply called “table mountains.”

Strictly speaking, mesas are isolated from the surrounding landmasses on all sides by erosional escarpments. For example, the Island in the Sky mesa in Canyonlands National Park is nearly completely cut off from the adjacent plateau, being only connected via a neck (a narrow strip of land) some 30 to 50 feet wide. More generally, a broad, flat-topped, isolated mountain that is bounded on at least one side by a cliff or steep slope is also called a mesa. South Mesa and Wilson Mesa, which sit above Spanish Valley and Mill Creek on the western side of the La Sal Mountains, are examples of these one-sided mesas.

|

| Named after the famed Civil War battleships, Merrimac Butte is on the left and Monitor Butte is on the right. Both are made up of the Entrada Sandstone |

Buttes are also isolated flat-topped hills or mountains. The word “butte” is borrowed from French, where it means a small hill or knoll. French explorers along the upper Missouri River introduced the term in the American west and it was later used by Lewis & Clark in their journals.

Informally, the shorthand description of the difference between mesas and buttes is that buttes are taller than they are wide and mesas are wider than they are tall. But a more accurate description is that mesas are simply bigger than buttes. Buttes are carved from mesas with continued erosion, and are often the last remnants of larger landmasses. Sometimes drainages form divides, separating buttes

from adjacent mesas, such as Junction Butte, which stands just off Grandview Point at the tip of the Island in the Sky. In other places, more isolated buttes such as the Bears Ears are all that remains of what had been extensive layers of hard sandstones that formed mesas that had covered that area.

|

| Candlestick as seen from the top of the Island in the Sky mesa. Note all the vertical joints in the Wingate Sandstone and the rockfall debris on the slopes beneath the cliffs. |

Some travelers to canyon country may be familiar with a different type of butte. Buttes are also small conical or pointed mountains with craggy peaks, especially in volcanic terrains. These buttes, such as Black Butte and Lava Butte in the Cascade Mountains in Oregon, not erosional features like the buttes in canyon country, but instead were built through volcanic eruptions.

Just as continued erosion will whittle mesas down into buttes, buttes will ultimately be reduced to spires. Spires, also called monuments or towers, are isolated rock pillars or pinnacles with vertical precipitous sides. The Needles, Candlestick and Fisher Towers are just a few examples of spires found near Moab.

|

| North Sixshooter Peak is a classic example of a spire capped by the Wingate Sandstone |

The terminology for the various types of rock

spires that exist on the Colorado Plateau is less systematic than it is for mesas and buttes. Some types of pinnacles, such as hoodoos, are delineated in the definitive geological reference (Glossary of Geology), while other commonly used terms are not. Hoodoos are fantastical columns of rock exemplified by the ones in Bryce Canyon National Park that form in thin rock layers with varying hardnesses. Monuments, such as those in Monument Basin in Canyonlands, are natural rock pillars that resemble man-made obelisks, while rock needles

have not been formally defined as a type of spire. The rock needles in Canyonlands were carved where erosion proceeds along two intersecting sets of joints in the hard Cedar Mesa sandstone.

The landscape around Moab contains the perfect ingredients for the formation of mesas, buttes and spires: the overall high elevation,

which yields topographic relief when carved by of the landscape by the Colorado River and its tributaries; the generally dry climate; and the layers of flat-lying sedimentary rocks. The hard Wingate and Entrada sandstones, which hold up most of the mesas, buttes and spires around Moab, might as well be called standstones: their resistance to erosion allows them to form vertical cliffs that form the landmasses that stand so tall above the surrounding desert.

You can read more geology articles from Allyson HERE

A self-described “rock nerd,” Allyson Mathis is a geologist, informal geoscience educator and science writer living in Moab.

A flat-lander by birth from where everything was covered with vegetation, Allyson is much happier exploring deep time in Moab and beyond. |

|

|