Geology HAPPENINGS September 2019 |

||||||||

| Capitol Reef National Park: Utah’s Geologic Wonderland by Allyson Mathis |

||||||||

To many people, a visit to Capitol Reef National Park means picking fruit in the historic orchards, hiking on the park’s great array of trails, and viewing Fremont Indian petroglyphs along the Fremont River. Nonetheless, like Utah’s other national parks, Capitol Reef is fundamentally a geological place; so much so that it is fair to describe Capitol Reef as Utah’s geological wonderland, a rare gem even among the state’s other geologic crown jewels. This history of referring to the Capitol Reef area as a wonderland goes back to the honorific “Wayne’s Wonderland” given by local residents and early park boosters in Wayne County in the early part of the twentieth century. All five national parks in Utah have great geologic significance: the abundance of natural arches in Arches NP, the stone spires (or hoodoos) of Bryce NP, and the canyons of Zion and Canyonlands. However, two aspects of Capitol Reef’s geology set it apart from these other spectacular parks.

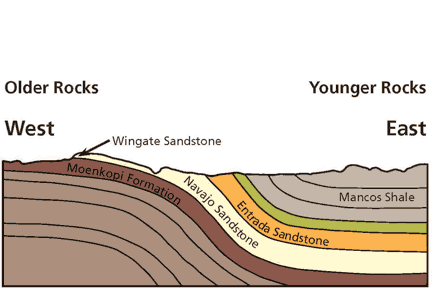

The other principle geological superlative of Capitol Reef is its huge thickness of sedimentary strata that provides a nearly comprehensive record of the Mesozoic Era (the Age of Reptiles) in Utah. A total of at least 18 different rock layers, known as formations to geologists, with a cumulative thickness of nearly 10,000 feet are exposed in the park. Capitol Reef’s rock record approximately equals that of Canyonlands and Arches national parks combined. If Capitol Reef’s rock layers were still stacked horizontally like those exposed in Grand Canyon, they would form a thickness nearly twice the canyon’s depth. At other sites like the Grand Canyon, hikers would have to ascend the trail from river to rim in order to achieve the same effect. On the west side of Capitol Reef NP, near the visitor center and along the Scenic Drive, the Moenkopi and Chinle Formations are capped by the Wingate Sandstone, e.g., the same units that at Canyonlands hold up the Island in the Sky. Younger rocks such as the Carmel Formation, Entrada Sandstone, and the Mancos Shale are exposed near the park’s east boundary.

The Navajo Sandstone is the most prominent of Capitol Reef’s rock layers. At Capitol Reef, the layer is approximately 1,000 feet thick and erodes into the park’s iconic white slickrock domes – including the park’s namesake, Capitol Dome, which is a rounded feature reminiscent of the U.S. Capitol building. The name “Capitol Reef” is the source of much curiosity for travelers in southern Utah, as many expect to encounter a coral reef similar to ones found in the Florida Keys, or least see rocks formed in a coral reef. While not made of limestone nor formed by the growth of reef-building organisms, the Waterpocket Fold created a line of cliffs that created an impediment to travel across it, somewhat akin to the barriers caused by coral reefs. The park’s name therefore reflects the two main components of its geologic story: the Waterpocket Fold and its signature sedimentary strata, including the Navajo Sandstone.

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

The first is the Waterpocket Fold, the 100-mile long buckle in the earth’s crust that defines Capitol Reef and is the park’s genius loci. Literally, genius loci means the “spirit of the place,” but in modern usage it indicates an area’s distinctive atmosphere. The Waterpocket Fold is the central feature of Capitol Reef NP, as park boundaries were roughly drawn to encompass it. Beyond Utah and the national park system, geologists consider this fold to be the best-exposed example of its kind on the earth’s surface.

The first is the Waterpocket Fold, the 100-mile long buckle in the earth’s crust that defines Capitol Reef and is the park’s genius loci. Literally, genius loci means the “spirit of the place,” but in modern usage it indicates an area’s distinctive atmosphere. The Waterpocket Fold is the central feature of Capitol Reef NP, as park boundaries were roughly drawn to encompass it. Beyond Utah and the national park system, geologists consider this fold to be the best-exposed example of its kind on the earth’s surface.