GEOLOGY HAPPENINGS October 2020 |

||||||||

| In Celebration of Moab’s Fossils: Petrified Woodby Allyson Mathis | ||||||||

National Fossil Day is celebrated in October each year to highlight the scientific and educational value of paleontology and the importance of preserving fossils for future generations. Given the realities of Covid-19, National Fossil Day planners have foregone a large public event this year. Still, everyone near Moab can have their own National Fossil Day commemoration by experiencing fossils in the “wild” as they are out enjoying canyon country (of course, in a safe and socially-distanced way).

Within the realm of paleontology, the Moab area is best known for its dinosaur fossils, although different types of invertebrate shell fossils and petrified wood are found in the area. The best places to see dinosaur fossils on public lands near Moab are two interpretive trails approximately 15 miles north of town. Dinosaur bone fossils can be seen along the Mill Canyon Dinosaur Trail. And the Mill Canyon Dinosaur Tracksite includes more than 200 individual tracks have been discovered from several types of dinosaurs. The understanding of ancient life would be incomplete if the study of paleontology only focused on the remains of large animals, regardless of the awe that dinosaurs inspire. For example, marine invertebrates help geologists understand varying oceanic and coastal environments as some species only lived in deep water, others in shallow water, and still others in the brackish water of an estuary. Likewise, plant fossils help geologists understand terrestrial environments.

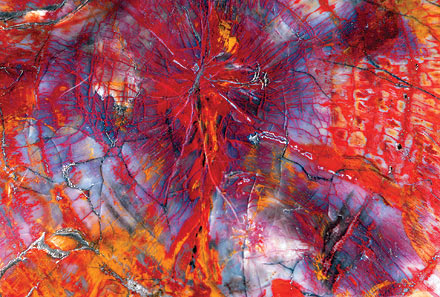

Circulating groundwater is usually the source for the minerals that are deposited during petrification. Silica in groundwater is readily derived from volcanic ash that can be deposited along with the other sediments that buried the ancient trees. Near Moab, petrified wood can be found in several rock layers (formations), with the Chinle and Morrison formations being most likely to contain petrified wood. Both these units were deposited in terrestrial environments, usually by rivers in their channels and on their floodplains. Many of these floodplains were forested, or at least dotted by trees. The Chinle Formation contains some of the most extensive deposits of petrified wood in the world, as exemplified by Petrified Forest National Park in Arizona. During Chinle Formation time (just over 200 million years ago), rivers flowed to the northwest through tropical forests growing on marshy floodplains that were also dotted by lakes. Most of the trees growing in these forests were of now extinct species of conifers, cycads, and ginkgoes, with some conifers reaching heights of nearly 200 feet. But the “forests” in Petrified Forest NP are not of these standing forests, but are the result of log jams of fallen trees that had been carried downstream by large rivers. The Chinle Formation contains some of the most extensive deposits of petrified wood in the world, as exemplified by Petrified Forest National Park in Arizona. During Chinle Formation time (just over 200 million years ago), rivers flowed to the northwest through tropical forests growing on marshy floodplains that were also dotted by lakes. Most of the trees growing in these forests were of now extinct species of conifers, cycads, and ginkgoes, with some conifers reaching heights of nearly 200 feet. But the “forests” in Petrified Forest NP are not of these standing forests, but are the result of log jams of fallen trees that had been carried downstream by large rivers. Coming across a piece of petrified wood while exploring canyon country is something worth celebrating, making any day an opportunity to appreciate fossils. It combines the joy of discovery, the appreciation of beauty, and the thrill of science. It is also a link to another time where instead of arid canyons and slickrock expanses, Utah was a land of humid forests where massive logs floated downstream in mighty rivers. All fossils on federal public lands are protected by the Paleontological Resources Protection Act because they provide important insights into past life. The Bureau of Land Management allows the collection of 25 pounds of petrified wood plus one piece per person per day for personal use with a maximum of 250 pounds per year, except in national monuments and other areas where collecting is prohibited.

|

||||||||

|