|

| Prince’s plume |

Exposed rock surfaces are one of the defining characteristics of the high desert near Moab. Expanses of slickrock, miles of cliffs underlain by rocky slopes, soaring rock domes, spires, arches and natural bridges, and a terrain cut by deep canyons, are the dominating features of the landscape in southeastern Utah.

But life abounds throughout canyon country; growing and living among, on, and around the rocks. Anyone who has spent any time exploring the landscape near Moab begins to notice the relationships between plants and geology here. Some of the connections are obvious, such as groves of cottonwood trees growing along streams, and the unique plants found near seeps and springs. Others are more subtle as some plants grow on specific rock layers or soil types. Prince’s plume, for example, favors alkaline soils containing selenium, and big sage tends to grow only on flats with thick alluvial soils.

Bare rock surfaces are mostly devoid of vascular plants, with the exceptions of those that take root in cracks (joints). Some of the weathered mudstones in the Chinle and Morrison formations are also mostly free of plant life because they contain swelling clays (bentonite). Plants don’t grow on them because bentonite absorbs water from precipitation, meaning that it is not available to them.

|

| Mike Duniway |

|

| Thin, rocky, poorly-developed soil in one of the USGS-NPS study plots. Photo courtesy of Chris Benson |

A group of scientists with the US Geological Survey’s Southwest Biological Science Center and the National Park Service led by Dr. Michael Duniway and Chris Benson recently conducted a study to further explore the connections and relationships between vegetation, bedrock geology, geomorphology (landscape features and erosion processes), soils, and climate in Arches, Canyonlands, and Capitol Reef national parks, along with the feedback loops between plants and soils.

The same geologic history that has created the spectacular scenery of the Colorado Plateau makes it a challenging environment for plants. Soil depth has a major impact on vegetation here. Many of the region’s soils are thin, lack substantial soil development, and contain a large proportion of rock fragments, especially compared to those in other places in the United States like the Great Plains where soils are thick, mature, and contain a significant organic component. The Colorado Plateau is erosion-dominated, meaning that the physical breakdown and transport of rocks and sediment occurs at a faster rate than weathering and soil formation processes (e.g., the chemical breakdown of rocks and formation of soil horizons).

|

| Chris Benson |

Duniway explained, “In other deserts of the southwest US, and really around the world, soil age can really shape what types of soils are found where, how productive plant communities might be, and what types of plants are where. The relatively young, erosional nature of the Colorado Plateau is generally not conducive to forming strong soil horizons (what we call pedogenesis), so what we see is here is a very strong influence of geology and geomorphology on the soils and the resultant plant communities.”

Benson added, “Perhaps one of the biggest ways that geology shapes vegetation communities is the topography that different types of rocks tend to produce. For example, the Wingate Sandstone almost invariably forms a tall cliff whereas the weaker shales of the underlying Chinle Formation form slopes which have comparatively much more vegetation than the vertical cliff walls.”

The rock types present in the region also has a major impact on plants. Sandstones are prevalent throughout canyon country, leading to sandy soils in many places. Other rock units, such as a Paradox Formation exposed in Salt Valley in Arches NP, and a facies (a lateral variation in a rock unit) of the Entrada Sandstone in Capitol Reef contain significant amount of salts, leading to saline soils. A different suite of plants consisting of greasewood, fourwing saltbrush, and some grasses grow in these soils than are found elsewhere.

|

|

|

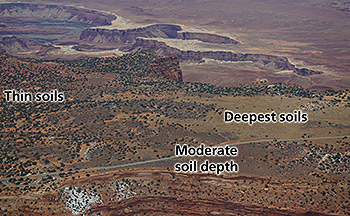

| Aerial photograph of the Island in the Sky showing the White Rim in the background. Areas with shallow soils are dominated by pinyon pine and juniper trees, whereas moderately deep soils support blackbrush, and grasses grow in areas of the deepest soils. Photo courtesy of Chris Benson. |

|

Chris Benson digging a soil pit in a blackbrush community in Arches National Park. Photo courtesy of Chris Benson |

Researchers also found that grasslands are found on deep, well-drained soils deposited by wind such as in Grays Pasture at the Island in the Sky and in the valleys of the Needles District in Canyonlands NP. “These deep soils support native perennial grasslands that are very productive and important for wildlife and were used intensively by livestock prior to park designation,” Duniway elaborated. “Though most areas like this in the parks are stable now, they are particularly vulnerable to wind erosion if disturbed, especially during droughts like we are in this year.”

The Colorado Plateau is both a unique geologic wonder, and also a unique biogeographic system where the interplay between geology, geomorphology, soils, and ecosystems shape its plant and animal life. The same dry climate and general lack of well-developed soils that plays such a major role in the development of the area’s spectacular scenery also makes it a difficult place for plants to survive. Research by scientists such as Duniway, Benson, and their colleagues not only aids understanding of these relationships, but also provide critical information for the management of the public lands surrounding Moab as the area experiences the current mega-drought and increasing public use, making it more difficult for plants to survive.

Special thanks to Mike Duniway and Chris Benson of the US Geological Survey.

|