|

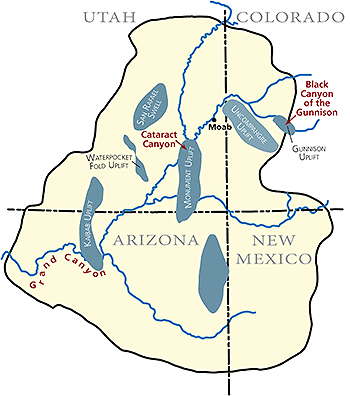

| Map showing some of the uplifts and canyons of the Colorado Plateau. |

Although it may seem like a paradox, the places on the Colorado Plateau that have experienced the greatest amount of tectonic uplift are also the locations of its deepest canyons.

The Colorado Plateau is one of 25 physiographic provinces in the continental United States. It is a high-elevation plateau characterized by vast exposures of mostly flat-lying sedimentary rocks in a landscape of mesas and buttes, and canyons carved by great rivers.

The iconic canyons carved by the Colorado and Green rivers and their tributaries are the most striking features of the Colorado Plateau. Grand Canyon in northern Arizona, Glen Canyon in southern Utah, and Canyonlands just south of Moab, are considered to be among the most scenic places in the world. In fact, the sublimity of its canyons is the main reason that the Colorado Plateau has the greatest concentration of national parks and monuments in the country.

The Colorado Plateau has an average elevation of more than 6,000 feet above sea level. The region was near or below sea level for much geologic past, as evidenced by its rock layers (formations to geologists) deposited in shallow seas, in coastal areas, and on river floodplains.

The plateau experienced at least three periods of uplift. The most important to our story of uplift and canyons occurred during a mountain-building event (the Laramide orogeny) that happened between about 70 and 40 million years ago. The Laramide orogeny raised the Rocky Mountains, as well as lifted the Colorado Plateau to an overall high elevation. Unlike what occurred in the Rockies, the Colorado Plateau was not extensively deformed and faulted.

|

| Cataract Canyon in Canyonlands National Park is approximately 2,000 feet deep and has walls mostly made of resistant limestone deposited near the end of the Paleozoic Era. |

Instead, the region experienced uplift that mostly left the original horizontal layering of the rocks intact. Although the rocks are mostly flat-lying on a broad scale, there are some gentle upwarps that elevated parts of the Colorado Plateau relative to other areas. These uplifts include the Kaibab, Monument, Uncompahgre, Waterpocket Fold, and Gunnison uplifts, as well as the San Rafael Swell.

The explanation for why the deepest canyons on the Colorado Plateau are located at these uplifts are twofold. First, their general land elevation is higher than the surrounding parts of the Colorado Plateau. High elevation is an essential ingredient for deep canyons since rivers can only downcut to their base level, which is sea level for drainages like the Colorado that reach the ocean.

It is not possible to get a deep canyon in low areas. Grand Canyon, which has a maximum depth of more than 6,000 feet, cannot exist without rims at 7,000 to 8,000 feet above sea level (the lowest elevation of the Colorado River at the foot of Grand Canyon is at 1,200 feet).

Secondly, harder rock layers have also been pushed up at these uplifts. The older rock layers on the Colorado Plateau (e.g., the ones that have been elevated the most at the uplifts) are, as a general rule, harder than the younger rocks that were deposited on top of them. Their greater resistance to erosion is not a result of age, but reflects how they were formed.

|

| The inner gorge of Grand Canyon is made of the 1,700 million-year-old Vishnu basement rocks, which are very resistant to erosion. The upper part of the canyon has hard cliff-forming limestones and sandstones, along with softer units that make slopes. NPS photo by Michael Quinn. |

The oldest rocks exposed in some of canyons that incise into uplifts, like in the inner gorge of Grand Canyon, Black Canyon of the Gunnison, and Westwater Canyon that cuts into the Uncompahgre Uplift, are metamorphic and igneous ones that formed during Precambrian time, approximately, 1,700 years ago. These crystalline granites and schists are much more resistant to erosion than sedimentary rocks. Rivers tend to carve gorges, a type of deep, narrow canyon, through extremely hard rocks.

Even the sedimentary rocks on top of Grand Canyon’s inner gorge and exposed Cataract Canyon are harder than the ones found near Moab and Green River. The sedimentary rocks exposed in Grand and Cataract canyons were deposited during a time when marine waters covered much of what is now the Southwest during the Paleozoic era. Limestones like those that make up Grand Canyon’s Redwall cliffs and the layers exposed in Cataract Canyon’s walls, were deposited in these seas. In an arid climate, limestone is more resistant to erosion than other types of sedimentary rock deposited in other types of environments, like the sand dunes of Arches National Park’s Entrada Sandstone.

|

| Black Canyon of the Gunnison is as deep as 2,700 feet and is carved entirely through very hard Precambrian metamorphic and igneous rocks similar to those in Grand Canyon’s inner gorge. |

The presence of these harder rocks is also important because they hold up rims of canyons versus allowing the land to just be stripped away by erosional forces. Grand Canyon would not be nearly as impressive without the hard Kaibab Formation, which is mostly limestone, holding up the North and South Rims.

The uplift of the Colorado Plateau occurred well before the Colorado River established its path to the Gulf of California, which took place during the last few million years at most. The nuances of the Laramide orogeny uplifts and the erosive power of rivers combined to form the great tapestry of the Colorado Plateau landscape, including its deepest canyons.

|