The name “pumpkin” originates from the Greek “pepon,” meaning, “cooked by the sun,” as in ripe. The fruit’s orangish color reflects this condition, and pumpkins have become the poster child for the last day of October – Halloween.

Although pumpkins are native to the eastern United States, there is one relative of the “cucurbits” that grows in the Four Corners Region. Going by the names coyote gourd, buffalo gourd, Missouri gourd or stinking pumpkins, this viney relative does not win any jack-o’-lantern contests.

The scientific name Cucurbita foetidissima refers to the plant’s aromatic nature: “foetidissima” means “the most smelly.” Botanists use the common name “coyote” as a modifier for wild plants with domestic relatives like coyote tobacco.

Coyote gourds bear rough-textured, triangular-shaped leaves that may reach 12 inches long. The leaves arise from long, prostrate vines draped across the ground. Borne near the tips are curled climbing tendrils, and the large funnel-shaped flowers with five lobes arise from the leaf axils. Gourd bees pollinate the solitary yellow flowers, diving into a blossom to obtain the pollen rewards.

The gourd’s rounded fruits are roughly 4 inches across and a pale lemon-yellow color when mature. Younger gourds bear greenish stripes that fade with age. Though the above ground foliage is noticeable, the extensive underground root system may weigh several hundred pounds.

Native American Uses

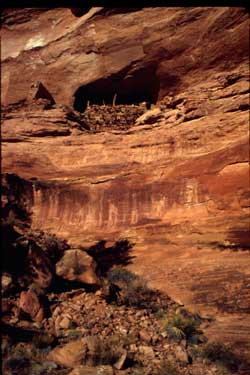

Found from southern California to Missouri, plants here in the Four Corners tend to grow in disturbed sandy sites along dry washes or in ancient gardens in close proximity to archaeological sites. Archaeologists have recovered parts of these plants in Ancestral Puebloan sites, indicating the plant’s use by native peoples.

The early Native Americans consumed the seeds and flowers of these gourds. Mature gourds were not eaten, but collected for their “soapy” properties. Containing saponin glycosides, the natives mashed the bitter tasting shells of the gourds to make a natural detergent. Today, the coyotes and raccoons avoid the fruit’s bitter pulpy mass.

The natives also passed on the leaves and roots, which contain rank-smelling chemicals, called cucurbitacins. Bitter and unpleasant, the crushed leaves made an insect repellant or a poultice for sores or wounds.

All Hallows Eve

During the time when the Ancestral Puebloans were living in the southwest, the Romans were staking claims throughout Europe. One aspect of the Roman’s culture, which pertains to the month of October, was the transition of the pagan holiday Samhain (pronounced “sah-win”) to the Christian’s observance of All Hollows Day or All Saints Day, which eventually became All Hallows Eve and then Halloween.

During the time of the Celts and Druids, the festival of Samhain marked the transition from summer to winter season. People believed that during this time a thin veil separated the worlds of the living and the dead. Perhaps to honor their dead or to ward off wandering spirits (history is a bit hazy here), the ancient Celts lit bonfires, donned animal skin costumes and declared prophecies for the coming year. It wasn’t until European immigrants coming to the New World in the 19th century did the modern-day concept of Halloween begin to emerge.

So maybe it is a stretch to tie together coyote gourds with Halloween, but these fruits are the closest native relatives to the domesticated pumpkin here in Canyon Country. I don’t think you’ll find any of the locals camped out in a stinking pumpkin patch wearing animal skins on Halloween while awaiting a visit from the Great Pumpkin. But then again, stranger things have been observed here during this pumpkin-crazed month.