PALEO HAPPENINGS July 2020 |

|||||||||

| Tracking Moab’s pterosaursby Martin Lockley, Moab Giants | |||||||||

Last month we ended our tracker’s report with “stay tuned for our next article, on the tracks of pterosaurs, turtles and other exotic creatures.” Imagine you are sitting on the banks of a Late Jurassic stream, watching a Stegosaurus: a splash and you spot a crocodile, and a fleeting shadow as a pterosaur flies overhead. Thanks to the famous Utah geologist, William Stokes, in 1957 the world learned of the first pterosaur tracks found in the Four Corners area. The tracks were from the dinosaur-rich Late Jurassic Morrison Formation, and Stokes named them Pteraichnus (meaning ‘pterosaur trace’). These trackways are very different from any made by dinosaurs, and so have caused some confusion and debate. Were they quadrupeds as the trackway indicated, or could they represent bipeds? Did they flop around clumsily like bats on the ground, or stand upright more like birds? The answer may seem surprising. Pterosaurs of course had wings, but not like birds built around finger number 2. Pterosaur wrists also had three short fingers as well as long wing fingers (the 4th). In the 1980s, two paleontologists claimed pterosaurs were bipeds and suggested the 1957 trackway represented a quadrupedal crocodile. The problem was that the trackway showed clear front footprints that match the robust pterosaur wrist bones.

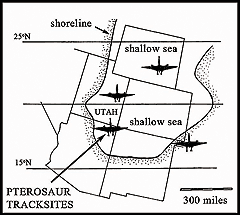

The debate would be resolved in favor of quadrupeds in the 1990s, when many Late Jurassic tracksites were found widely across the western USA: in Utah, near Moab, in Colorado, Wyoming and Arizona. Typically these tracks were only 2-4 inches (5-10 cm) long. More tracksites were soon found elsewhere around the world, in both the Jurassic and Cretaceous. Some tracks were large, up to 12 inches (30 cm) long. Almost all indicate quadrupedal progression. Pterosaurs had very short hind legs with slender-toed, webbed feet, better for paddling than upright walking. On the other hand, they had powerful wings and wrists, and could fold their wings back into what would be their arm pit, or wing pit, areas while supporting most of their weight on their strong wrists. In fact, front footprints are often deeper than the back footprints. This indicates the weakness of the hind limbs. Trackers find many tracks, connected to long scratch marks that indicate pterosaurs floating in shallow water, scraping the bottom, as some birds, like gulls, do today. Many layers contain traces of invertebrates, such as worms and shrimp, on which the pterosaurs probably fed in shallow water deposits representing ancient marine shorelines, lagoons, or lakes: imagine Moab’s ancient seaside with pterosaurs floating not far offshore.

|

|||||||||