PALEO HAPPENINGS October 2020 |

|||||||||

| The Sex Life of Dinosaurs: The Evidence by Martin Lockley, Moab Giants | |||||||||

‘Tis said that “birds do it and bees do it, even educated fleas do it.” So, dinosaurs did it, and as Ella Fitzgerald sang in Cole Porter’s song, they said to one another “Let’s fall in love.” As promised in the September issue, this article is devoted to the ‘evidence’ for the sex life of dinosaurs, and specifically the theropods, now famous as bird ancestors. We now know that various, mostly- small, theropod dinosaurs had colored feathers and even wings. With the bird-theropod relationship firmly established, paleontologists became Mesozoic bird watchers, paleo-ornithologists. Why did these dinosaurs have colorful, eye-catching, feathers and crests instead of drab scales? Was it to attract mates? Yes! Why not? The peacock and birds of paradise are inveterate show-offs, (the males of course), dressed up like dandies. The birds of a feather connection to dinosaurs spawned a considerable, highly speculative literature on what dinosaur courtship was like back in the Mesozoic. But honestly, this well-educated conjecture, although consistent with bird behavior, it was pure speculation. There was no physical evidence other than feathers, which could simply be for insulation, and crests, which many dinosaurs did without.

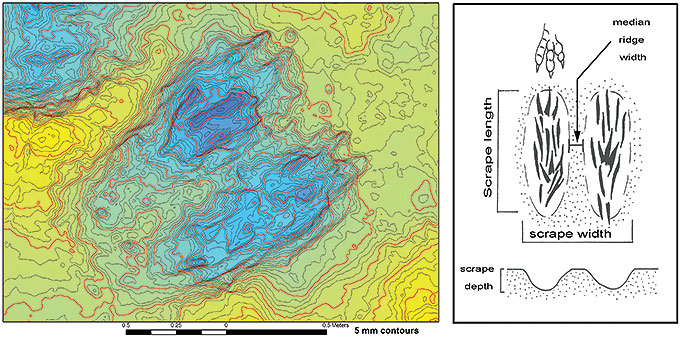

The physical evidence, in the form of large scrape marks, was stumbled upon by two amateur trackers from our research team who had already found tracks in 100-million-year-old Cretaceous rocks in western Colorado. The scrape marks look just like what ornithologists call “nest scrape display” traces, made by male birds showing their breeding partners their nest building abilities, a behavior known as “lekking.” A “lek” is a congregation of male birds assembled for competitive courtship displays, a bit like vote-for-me electioneering! The difference between mostly-small, nest scrape display traces made by modern birds, such as ground nesting plovers, is that the Cretaceous theropod dinosaurs gouged huge scrapes, some six feet long, three feet wide and a foot deep, in sandy substrates known as “display arenas.” (“Arena” comes from the Latin word sand: think of coliseum gladiators). Modern birds congregate in the emotionally charged Spring breeding seasons, to begin territorial breeding and nest scrape display behaviors. Dinosaurs made multiple scraping attempts, gouging two left and right furrows with clear claw traces on either side of a median ridge. None of these were used as nests which would have smudged out the scrape marks if they had settled in for egg laying and incubation. But after attracting a mate the pair would have nested nearby, meaning paleontologists can hope to find nesting colonies nearby, if still preserved, or at least known where they could be found. In western Colorado there are now three known display arena sites each with between 15 and 50 scrapes. If fully visible, these surfaces would likely expose hundreds of scrapes.

|

|||||||||