Reyes Madalena

Reyes Madalena |

Why do some people have a gift? Why

can some people create music out of metal, or art out of

pigment, or pots out of clay? Why are some people sublimely

talented while others struggle in the same area?

It seems to be a randomness of genetics. Yes, some families

appear to carry an art gene that gets passed down from

one generation to the next, but even within those families,

why does one sibling get it and not the others. It seems

to be as random as the passing on of a recessive gene that

pops up from time to time, causing relations to exclaim, “why

the baby is a carbon copy of Great Aunt So-and-So!”

After all, isn’t that the basic explanation of how

you would end up with a naturally sunlight-blonde Native

American.

When Reyes Madalena, a Jemez (pronounced “Hay-miss”)

Reservation Pueblo, laughed on the phone while telling me

she was blonde, I wasn’t sure who the joke was on.

Apparently it’s no joke. She’s a hundred percent

indigenous to this land, and she’s blonder than most

of us (including our artificial highlights). She’s

just got light pigmentation, one of those random blips in

a family gene pool that surfaces unexpectedly.

This unusual coloring considering her ethnicity is not the

only thing that connects her to the rich tapestry of her

ancestry. Another thread that reappeared in Madalena was

her grandmother’s talent with clay. Madalena is a potter.

Now, when I say “potter,” I don’t mean

someone who buys clay, throws it on a wheel and paints it

with glazes, which is no small feat to begin with. Ask anyone

who’s tried, and, most likely, struggled.

No, I mean “potter” in the sense that her ability

to craft clay into art is written into her DNA, much like

her gender, height and skin color are. She inherited this

gift. It literally emanates from her fingertips.

As we talked, she maintained eye contact with me the entire

time she manipulated a ball of clay around and around in

her hands until a well-shaped, symmetrical bowl emerged.

She never had to look at what she was doing. She created

out of touch, not sight.

This connection Madalena has with the earth (after all, that’s

what clay is) and her art is part of what makes her pottery

so magic.

You could identify the physical reasons why her earthenware

is so smooth, resists cracking and burnishes to such a splendid

sheen. Pottery, in its essence, is chemistry in action. And,

like any good cook, a good potter needs to know how the clays

will react, particularly under the intense heat of a firing.

But, analyzing the chemistry of pottery is like analyzing

the chemistry of a person; it may explain their unusual pigmentation,

for example, but it doesn’t capture how that color

has shaped the person.

In Madalena’s case, growing up on one of the few continuously

inhabited pueblos, her singular look galvanized her to embrace

her heritage more fervently than the others.

Born in the late 1930’s, she grew up with the other

Reservation kids calling her “white girl,” which

made her dream “that someday I’m going to do

something really Indian,” she recounts.

And, sure enough, she’s the only one of her childhood

friends who became such an accomplished potter.

To be fair, Madalena had the advantage of genetics on her

side. Her maternal grandmother, Benina Medina Madalena from

the Zia Reservation, had been an excellent potter, winning

awards in the early 1920’s at the Santa Fe Indian Market.

She was the one who essentially reintroduced the art to the

Jemez Reservation, where the craftsmen had focused on other

indigenous crafts.

Benina taught her daughters pottery which created a wonderful

beginning for Madalena, who remembers watching and listening

to her mother and aunt making pots. Although they were accomplished,

the natural talent Benina possessed resurfaced in Madalena,

who uses the same techniques, the same clay sources and the

same smooth red jasper stone to burnish her pots to a high

sheen.

The inheritance of this particular river stone symbolizes

the passing on of the knowledge and gift for pottery-making,

from grandmother to grand-daughter.

Madalena, whose sensitive skin doesn’t tolerate synthetic

materials, uses all natural clays and slips. She and her

immediate family mine the rock clay themselves, which includes

hauling out 100-pound packs on foot over rough trails. One

of her greatest moments was discovering the seam of gray

clay found in the Four Corners area that yields the fine

white pottery which much of her current work is made of.

For decades, she searched for its origins. Most clay fires

up a reddish or brownish color, so this white clay that her

ancestors used was a momentous discovery. Because of this

clay’s purity, Madalena is fairly sure that she’s

mining the same seam as her ancestors, and this connection

excites her.

She also feels connected to the past by using traditional

methods. She processes the clay herself, aided by her husband.

After soaking the rock for several weeks to soften it, she

mixes it and, then, allows it to evaporate in burlap bags

until it arrives at the desired consistency.

She shapes the pot either by pinching the clay while rotating

it methodically (called a “pinch pot”) or roping

long coils of clay on top of one another and smoothing the

surface (a “hand-coiled pot”), which usually

leaves a slightly ridged interior.

The latter technique allows Madalena to create pots of varying

size. Possibly her most impressive piece, the “Ancient

Style Water Canteen Storage Vessel” is a 24-inch diameter

orb with handles and a mouth. Because the vessel sports a

rounded bottom, it is hung by its rope handle. A mirror under

the canteen reflects the finely detailed white buffalo depicted

on the underside of the canteen.

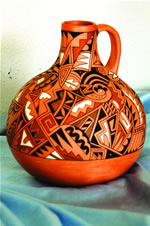

The majority of the pot is decorated with tiny triangles,

in white, rust and black, that form multiple patterns, horizontal

and zigzag, much like a quilt. The design encircling the

rim displays even smaller designs, evidence that Madalena

does not sacrifice fine detail to the large size of the piece.

Both the designs and the types of pots she creates are also

tied to the traditions of her Anasazi ancestry. Madalena

uses different color clays to decorate the pots. She designs

spontaneously on her pottery; however, she always incorporates

certain familiar motifs that date back thousands of years

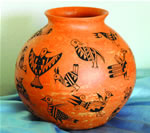

and have well-established significance.

For example, the ever-present step motif represents the lightening

in the sky, while the parallel lines that usually appear

on one side of the steps represent rain. Another common design

is that of a bird represented by a triangle made up of slightly

curved lines with a circle in the middle. The traditional

designs appear on all her pottery, blended in a variety of

ways according to the artist’s inspiration.

In addition to canteens and cooking pots, Madalena creates

bells, wedding pots (which have two spouts, symbolizing the

union of a couple) and gourd-shaped vessels. These are all

useful items, particularly for an agrarian lifestyle, which

is evidence that form blossomed out of function. Her decorative

items, however, include storytellers, figurines and bells,

favorites of many collectors.

The final step in creating pottery is the firing, which is

the test of how good the clay and the potter are. Because

of the intense heat required in baking clay, if the clay

is not the right consistency or dryness, or if the potter

has not worked the clay properly, the contracting process

that the earthenware undergoes will show cracks or break.

Like in every other aspect of her art, Madalena avoids shortcuts

and modern methods for the traditional ones. Although she

purposely keeps the details vague to preserve trade secrecy,

she reveals that she burns cedar wood in her hand-built firepit.

Few of us are really as defined by our professions as the

language we use implies. We say “he is a fireman,” or “she

is a teacher,” when what we mean is “he puts

out fires for a living,” or “her profession is

teaching.” In Madalena’s case, being a potter

is very much at the central core of who she is.

Now in her late sixties, she continues to toil at a physically

demanding art, considering that she processes her own clay

and paints in such small, accurate patterns. Yet, she does

so with the passion and devotion that clearly gives joy and

meaning to her existence.

Not only does she produce beauty through her art, she sustains

an important connection to her past. Would her art be less

valuable if it were created by a non-Native American? Probably,

since collectors care about authenticity. But, even more

importantly, Madalena cares about the preservation of her

culture and its traditions.

Clearly, what makes her “Indian” is not dependent

on the color of her skin, any more than a Frenchman must

wear a beret, but it is the strength of the tie to her heritage.

The energy of former Pueblo potters runs like a river through

this area, and by clutching at this particular piece of red

jasper, she has anchored herself in it and the energy flows

through her and in to her marvelous creations.

Reyes Madalena uses her home in Moab both as a studio and

gallery. To make an appointment to view her earthenware,

she may be contacted at (435) 259-8419. For large enough

parties, Madalena is willing to do a demonstration of her

pottery-making. |