Above

me the night sky glitters with the sparkling shards of a

thousand points of light. The clarity is crystalline – just

another typical night sky here in southern Utah. A new moon

hangs suspended in the western sky as if snagged on the sharp

spine of a star.

But I don’t take this purity for granted. I appreciate the scarcity

of lights that would otherwise detract from this image. The only lights

I can see are the occasional red brake lights of late-night descenders

heading off the mountains, as well as the beam of my headlamp as I continue

my search for nocturnal moths of the yucca kind.

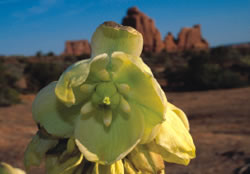

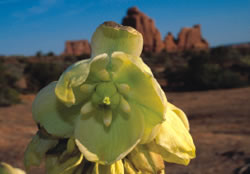

I illuminate the wands of yucca flowers that stand out like desert lighthouses

with my headlamp. The moon-white flowers are easy enough to see without

the light, but the headlamp helps to avoid the bayonet-sharp leaves as

I examine the flowers up close. My goal this April evening is to observe

a nocturnal performance, perhaps not as old as the stars above, but one

that is just as intriguing.

Over thousands of years, the relationship between the yucca moth and

the yucca plant has grown strong. So strong, that for many species of

yuccas there is only one specific species of moth that pollinates their

flowers. Without the tiny moth’s fidelity to the flowers the plant

can not reproduce. Without the yucca seeds, the larvae will starve. This

mutalism is based upon an exchange, a bartering system for services rendered.

It all starts when a female moth visits a flower and gathers a ball of

sticky pollen grains with her specially designed mouthparts, called palps.

Lacking talons or teeth, the moth carries this ball between her tentacles

and her thorax, much the way a child would carry a ball beneath their

chin. From here, the female leaves and searches for another individual

yucca whose flowers are ripe for pollination. There she lands on the

silky outer petal-like tepals and crawls down the pendulous flower and

disappears into the inner chamber of the flower. She continues to the

stigma, the female structure that receives the pollen. Here she jams

the pollen mass into the stigma in a deliberate act of pollination.

So why does this moth seek only the yuccas and not other night blooming

plants like the evening primrose or sand verbena? After the female plants

the pollen, she then deposits one or more of her fertile eggs into the

flower’s ovary. She must penetrate the outer wall of the ovary,

which is not very thick, but still she must commit a floral felony. With

her ovipositer she deposits an egg within the ovary chamber of the flower.

Over time, as the yucca’s ovary develops and the seeds start to

ripen, so too does the moth’s larva. The ovary plays nursery host

to the larvae, who feed upon the yucca’s seeds. When the larvae

mature in late summer or fall, they exit the seedpod and either rappel

down on a silken thread or simply drop like stones to the ground below.

From here they crawl to a nearby spot where they will burrow underground

to form a cocoon and pupate. They will overwinter in this earthen womb,

some ¼ - 1” below the surface. Though the larvae generally

emerge the following year some may stay underground through a second

winter.

The following spring the adults emerge pushing up through the desert

sands. I’ve never witnessed this segment of the moth’s life

cycle and am not sure if I ever could. I would have to either catch pod-emigrating

larvae or dig some soil from around the plants and hope they contain

the larval seeds. I would have to place the soil in a terrarium and await

the return of spring and the emergence of the moths. But until then I’ll

just have to appease my natural history soul by wandering about the desert

at night with only my headlamp and curiosity to illuminate my way.

|

|