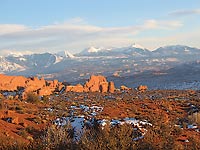

Red rock. Slickrock. Sandstone. No matter what you call it, the colorful landscape of southern Utah is dominated by expanses of red rock. The canyons and hoodoos, arches and bridges, spires and buttes are the main attractions in the region. But don’t forget those high peaks, the lofty mountains that create a silent backdrop to such scenic wonders as Delicate Arch or Balanced Rock – the La Sal Mountains.

Red rock. Slickrock. Sandstone. No matter what you call it, the colorful landscape of southern Utah is dominated by expanses of red rock. The canyons and hoodoos, arches and bridges, spires and buttes are the main attractions in the region. But don’t forget those high peaks, the lofty mountains that create a silent backdrop to such scenic wonders as Delicate Arch or Balanced Rock – the La Sal Mountains.

Spaniards named these peaks. In 1765, Juan Maria Antonio Rivera led an expedition up into the region from Santé Fe. They named the snow-capped peaks the La Sals, which means “the salt,” for either salt outcrops in the foothills that the Native Americans harvested, or for those snow fields which the Spaniards may have mistaken for salt fields. Almost a decade later in 1776, two Franciscan priests, Francisco Atanasio Domínguez and Silvestre Vélez Escalante led an expedition through the region, trying to find an overland link from Santé Fe, New Mexico to Monterey, but left names on many canyons and other features.

Many other Spaniards passed by these peaks over the years, traveling the Old Spanish Trail with trade goods from Santé Fe to their destination in California.

Many other Spaniards passed by these peaks over the years, traveling the Old Spanish Trail with trade goods from Santé Fe to their destination in California.

Fast forward to 1877. Albert Charles Peale (1849-1913) was a geologist and mineralogist on the US Geological and Geographic Survey of the Territories. He served on several western mapping expeditions led by Ferdinand Hayden, and described the geology of the La Sal Mountains. The highest peak in the middle range at 12,726’ is named Mt. Peale in honor of this geologist.

Peale and subsequent geologists have determined that the La Sals have a broad igneous core that intruded into overlying sedimentary rocks, finding fractures and zones of weakness to fill. Unlike the stratovolcanoes of the northwest, this igneous intrusion did not erupt, but forced the overlying layers upward, fracturing them. Three centers, known as laccoliths, aged around 25 to 30 million years old, resulted in distinct north, south and middle ranges.

These high peaks were glaciated during the Pleistocene multiple times. Though no glaciers exist today, evidence of these glaciers can be found in various locations.

Beyond this geologic base, the La Sals are a Shangri La that complements the red rock landscape that skirts the peaks. Cool in summer and snow-clad in winter, this range is home to many species of wildlife including deer, elk, bear, cougars, small rodents, birds and reptiles. Forests of aspen, spruce, fir and pine cloak the higher elevations, while oak woodlands and mountain brush stretch downward into the foothills.

Beyond this geologic base, the La Sals are a Shangri La that complements the red rock landscape that skirts the peaks. Cool in summer and snow-clad in winter, this range is home to many species of wildlife including deer, elk, bear, cougars, small rodents, birds and reptiles. Forests of aspen, spruce, fir and pine cloak the higher elevations, while oak woodlands and mountain brush stretch downward into the foothills.

So what does it all mean? Especially with winter at November’s door and early snows dusting the peaks. The trails are quiet, empty of summer’s footsteps. The wildlife is moving, downward into winter ranges or in search of hibernation dens. Late migrant birds catch updrafts on their way south, while others move in for winter. Carpets of decaying leaves mix with the last holdouts recently abscessed. In short, November is a great time to explore the history, geology and wild nature that exists in these mountains or appreciate their backdrop from the canyons below.